Take Action Today!

Tell your governor to grant clemency to those currently incarcerated for cannabis-related offenses and expunge past cannabis arrest records. Legalization without justice is HALF BAKED!

Crystal Munoz was a happy mother to a months-old baby girl. She was pregnant with her second daughter. She and her husband were working hard to start a screen-printing business. Then Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) agents knocked on the door of her Texas home. They assured her that she wasn’t in trouble. They just needed her help. Could she answer some questions about some people she might know?

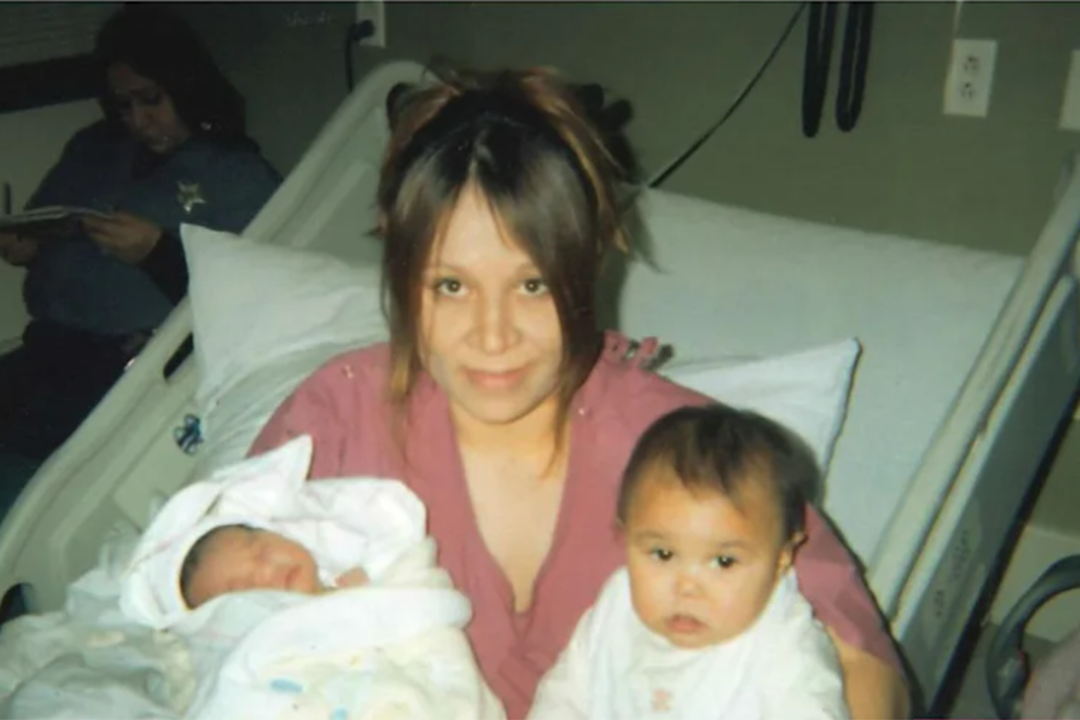

That conversation led to a profoundly unjust marijuana conviction and a 20-year prison sentence. (After serving almost 13 years, she was given clemency in 2020.) It devastated her family. Ms. Munoz had to give birth to her second daughter while shackled to a hospital bed. How could this happen? And why—in a country where cannabis is now legal in dozens of states—are so many thousands of people still getting arrested every year on cannabis-related charges?

Ms. Munoz told us her story with the hope that it might help others and shine a light on the injustice so many are still experiencing.

Tell your governor to grant clemency to those currently incarcerated for cannabis-related offenses and expunge past cannabis arrest records. Legalization without justice is HALF BAKED!

You’ve been through a lot. Can you tell us how it all started?

I drew a map. It was not a sophisticated map. It was on a regular piece of notebook paper. It was a couple lines and a couple of arrows. Some people I knew asked me to draw it because there was supposedly a ranch dispute among the ranchers and some people who gave these ranchers money to use their ranch. And the ranchers took the money and didn't hold up their end of the bargain. So I thought it was a cattle dispute, something about cattle.

It was only afterward that I put 2 and 2 together and realized that they were using the ranch road to transport marijuana.

Two years later the DEA came to me and asked to talk. They assured me I wasn’t in any trouble, that it wasn’t about me. They just wanted some help and some information. The DEA showed me pictures, including pictures of those people I’d known. They didn’t ask me any questions about those people, they just wanted to know if I knew or recognized anybody. I told the truth and said that I recognized them. The DEA used my honesty against me.

What happened next?

The original indictment was conspiracy, A, to possess and distribute a thousand kilograms or more of marijuana. And B, conspiracy with intent to possess and distribute 50 kilograms of cocaine or more. And then C, the same conspiracy with intent to possess and distribute five grams or more of crack cocaine. It was crazy. A conspiracy? I had no idea.

I found out later, doing research in prison, that anybody can be charged with a conspiracy just based on hearsay. Law enforcement doesn’t even need solid evidence. Their evidence can be what they call in legal terms circumstantial.

Those people I’d recognized, they were arrested about two years before the DEA came to see me. They were given sentences of 5-10 years and were caught with only marijuana. So, ultimately, the prosecutors put in a motion to withdraw sections B and C of the indictment, which left the marijuana by itself. The marijuana quantities alone held a life sentence on the federal drug chart, but it didn’t matter. Of course I pleaded not guilty.

That must have been so frightening. What was the trial like?

Around the time that the DEA knocked on my door I had just given birth to our first daughter and she was maybe almost three months old. I was also about one month pregnant. My husband and I were just trying to start a screenprinting business and we didn’t have the money for a lawyer. So we got a court-appointed lawyer.

My dad is white and my mom is Native American. Most people mistake me for a Hispanic. My husband is Hispanic. My last name is Munoz. And when my lawyer found out that half of my family was white, he said to me, "I know this is going to sound kind of messed up, but can you please try to bring as much of your white family as possible into the courtroom during your trial?" He said it because he knew that Black and Brown people are arrested more often and tend to get much longer sentences than white people.

But in the courtroom, it was just me and my husband and my grandmother—who is white but doesn't look white. And I got 20 years. They actually said I was a leader and an organizer because I drew that map of a ranch road.

At what point did you begin to realize that what you were going through wasn’t some kind of an awful misunderstanding, but that the system itself was the problem?

Really, it was right away, when they started threatening me. I was being honest with them, but they turned it around on me. By the end of that DEA interview I was crying because they started threatening me, saying things like I'm not going to see my baby anymore if I didn’t give them any information. That was the moment that I realized how broken the system is.

They gave me a 20-year sentence, after threatening me with a life sentence, and I was never even caught with any drugs! And the people who WERE caught with drugs were given 5-10 years! What they did to me I consider a heinous crime. Taking a mother away from her newborn baby…

My girls didn’t experience having me and I didn't experience being a mother to them. That is so hurtful. It’s the most gut-wrenching pain to lose a child—I also lost our firstborn, a son, when he was five. He choked to death at school. It was an accident. But that is the most hurtful, gut-wrenching pain to experience in life. And that was comparable to being taken away from my babies. That’s what the system did to me.

And you had to give birth to your second daughter while you were incarcerated.

Yes, while they had me cuffed to a bed. And then they took her away. They allowed me to stay with her in the hospital for a day, with two DEA agents outside my door and one inside the room with me. So I'm there trying to hold my then 10-month-old and my newborn all night, all day until I have to leave because I don't want to miss a blink.

After these experiences, how does it feel to see cannabis legalized across the country, while hundreds of thousands of people, most of them Black and Brown people, are still getting arrested for cannabis every year?

It really is an injustice. There has to be a better way. I mean, they have so many intelligent, educated people in the Congress, in the justice system, in the sentencing commission, in the Bureau of Prisons to come together and put their minds together and say, "This is not working. Here’s a solution."

But these entities, they don't work together. In my situation, I get incarcerated. They hold me in a federal holding facility, in a county jail. The authorities in the county jail, they don't like the authorities in the FBI. The FBI, they don't like or listen to the authorities and the DEA. And then they ship you to the Bureau of Prisons. The Bureau of Prisons doesn't respect the authority of the court system. The court system and Congress don't work closely with the people in the sentencing commission. They all don't respect the authorities of the other entities, but they're all connected like a chain.

So states are legalizing marijuana, but with the fear of being prosecuted on a federal level, because the federal level doesn't respect the authority of the states and vice versa. It's not working. It's a broken system.

What did you learn about the system while you were incarcerated?

They took 12, almost 13 years of my life. I could have been building my life, contributing, paying taxes, and instead I was being babysat by adults and it was being paid for by taxpayer money all that time. Just sitting there doing nothing, just waiting for something to happen to change my situation. Every day I waited, thinking “Something has to happen. Something has to happen. Call this person, call that person." I was filing motion after motion after motion in an overloaded court system. One judge has several stacks, maybe three-feet-high stacks on his desk every day. He can never realistically ever look over each and every case. He’s just having his court assistants stamp deny, deny, deny, deny, deny, deny, deny.

The other thing is, if you compare mine with other cases, there's other judges in other states and other parts of this state that have given people less time for doing worse than what I did, people who were actually caught with a thousand pounds of marijuana getting less time than I did. It's because you got a different judge that has different morals. You got a different overzealous prosecutor that's brand new. He wants to make a name for himself. He thinks he's doing something good. But really, they’re just playing with people's lives.

You were granted clemency and released from prison about two years ago. What did it feel like when you were finally reunited with your family?

I think I was in shock for probably over a week. And shock is the only word that I know to describe it, because you think you would have all these emotions, you would have this extreme joy, you would have this extreme gratitude, you would maybe cry. But for me it was as if I was feeling nothing—like I couldn't feel anything. I was just trying to absorb that reality because it's almost as if it wasn't real, but it was real.

Not very many days after I was released from prison, I was invited to the White House. It was hard to process. Everything was. My friend, Alice Johnson, was also given clemency, about a year before I was, and she said, it's like going down in a submarine and you're down there for a decade or however long it was and you come back up. Then, all of a sudden you're up here now. And you're not down there anymore. And everything is different.

How have you been adapting?

COVID has lessened the shock because, let me tell you, COVID made this world seem a little like a prison camp. Because I spent many years behind a fence inside a real prison. So out here when I came home, the pandemic's been going on and I've been secluded with my family. I feel like it would've been way more overwhelming had COVID never existed.

I realize how prison has affected my personality. If I'm in a crowd of people now, I'm not outgoing and I'm not going up to people and trying to talk to them or hug them. I want to, but I refrain from doing that because in prison, you can't. You're not supposed to touch another person because you could get in trouble. You could get an assault charge put on you if you barely touch an officer. And they don't even want you to hug your kid when they visit you. You can only hug your kid once when they come in and once when they leave. That's the only time you can hug them, your own family.

When you're in prison for years and years, it takes you some time after you get out to kind of realize, "Hey, I don't have to feel this way any more." But it affects you and you feel uncomfortable doing things that are normal. Prison dehumanizes you.

What do you think needs to happen so that nobody else ever has to go through what you’ve experienced?

People have to have empathy. People in power. They have to be able to put themselves in another person's shoes and ask, what is the solution? And is that right?

When I was in prison I would often think of the injustices and try to comprehend how or why. How does this work? But then really it doesn't matter how hard you try to make sense of it—you never can. And so I would often think to myself like, if only judges or lawmakers could go and sit and see and feel everything that a person goes through whenever they're indicted and incarcerated, from the court system to the prison system, to all of it. It's just traumatizing.

You know those virtual reality headsets that you can put over your eyes and it looks like you're in this whole other world? Imagine if a judge, a congressman, a senator, or the president could put that on and they could be walked through that experience. Because unless it really happens to you or somebody very dear and close to you, then your eyes are not open. Your heart is not open.

How would you describe your experience?

I compare it to being buried alive because it feels like you're dead. You're dead, but you're alive. And the grieving process that the families go through and that you go through is like death. You can't get to them. They can't get to you. Life goes on. You're trying to still remain part of the life out here. But really you can't.

My husband and I stayed married all these years, and I don't even really know what it would be like not to have somebody that supports you like that. It would be incredibly hard. It was still very hard. But he tried to come visit me every time he had enough money to travel, stay two nights, eat. He wound up spending about a thousand dollars each visit, with the travel and hotel and all that. That's a lot of extra money to have to come up with. If you have a family that has money and they're close by and they could come visit you every weekend, that's great. It makes it better. But it's still not enough. It destroys families. It feels like you're dead, but you're alive.

It’s hard, but I'm honored to be talking about all this because it's going to help me heal. If my story can help someone understand what it’s like, if it can lead to a change in the laws, then that'll help me make some kind of sense out of it.

Tell your governor to grant clemency to those currently incarcerated for cannabis-related offenses and expunge past cannabis arrest records. Legalization without justice is HALF BAKED!